I feel old today.

Believe it or not, it’s been 100 years since Louis Blériot flew across the English Channel on July 25, 1909. The Daily Mail had a contest going on for the first success crossing of the Channel by aeroplane, with the winner receiving a £1000. It might seem like a small feat to cross the roughly 22.5 miles by air, but remember, this was less than six years after the Wright brothers made their first flight of 120 feet. Even at that, aviation really didn’t begin to take off until 1905. Consequently, this contest represented an important step every bit as impressive as Lindberg’s solo flight across the Atlantic only eighteen years later.

Hugh Latham decided he would give it a try first. Always a daredevil, Latham had tried his hand at speedboat racing and even wrangled a hot air balloon across the Channel in 1905. At night! Napoleon would have been proud; not only had he once considered the same, but Latham was French by birth. This time, however, was a more serious matter; his physician had advised him that he had but months to live. Never one to go gently into that good night, Latham decided he would rather go out with a bang. When a friend told him aviation was a dangerous sport fit only for the suicidal, Latham learned to fly.

Hugh Latham decided he would give it a try first. Always a daredevil, Latham had tried his hand at speedboat racing and even wrangled a hot air balloon across the Channel in 1905. At night! Napoleon would have been proud; not only had he once considered the same, but Latham was French by birth. This time, however, was a more serious matter; his physician had advised him that he had but months to live. Never one to go gently into that good night, Latham decided he would rather go out with a bang. When a friend told him aviation was a dangerous sport fit only for the suicidal, Latham learned to fly.

A friendship with a genial French engineer named Léon Levavasseur led Latham to select the elegant Antoinette monoplane as his mount (the series of aircraft took their name from the daughter of an industrialist backing the enterprise). The Antoinette series reflected Levavsseur’s philosophy, an solidly-engineered aircraft which eschewed the then-common wing-warping control technique in favor of true ailerons. The result was a stiffer wing and faster response. The surfaces themselves were moved by cables connected to a wheel and geared mechanism, allowing easy control no matter the breeze.

A friendship with a genial French engineer named Léon Levavasseur led Latham to select the elegant Antoinette monoplane as his mount (the series of aircraft took their name from the daughter of an industrialist backing the enterprise). The Antoinette series reflected Levavsseur’s philosophy, an solidly-engineered aircraft which eschewed the then-common wing-warping control technique in favor of true ailerons. The result was a stiffer wing and faster response. The surfaces themselves were moved by cables connected to a wheel and geared mechanism, allowing easy control no matter the breeze.

The Antoinette had a streamlined forward fuselage shaped like a boat (seen in this photo of a Russian-owned model). Latham reckoned this would come in handy in the event of a forced water landing. And indeed, it did serve that purpose well.

The Antoinette had a streamlined forward fuselage shaped like a boat (seen in this photo of a Russian-owned model). Latham reckoned this would come in handy in the event of a forced water landing. And indeed, it did serve that purpose well.

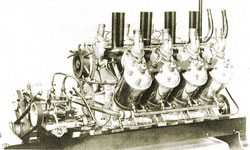

To power his aircraft, Levavasseur had crafted a beautiful engine for the Antoinette. This was the latest in a line of water-cooled V-8 engines, initially inspired by another early aviator, Clément Ader. The design had proven quite successful; indeed, one of his engines powered Alberto Santos-Dumont’s 14-bis, credited as the first controlled powered aircraft in Europe.

The lightweight engine coaxed 45 horsepower from around 7.2 litres of displacement. The design used a simplified crankshaft which let two opposing pairs of pistons share the same wrist pin. As a result, the crankshaft was both shorter (minimizing vibration issues at speed), and lighter. Levavasseur also had developed a simple fuel injection system that fed the cylinders equally and proved an excellent fuel-air mixture in theory; in practice, however, it proved extremely sensitive to the slightest contamination…dirt, a small bug, or other detritus.

The lightweight engine coaxed 45 horsepower from around 7.2 litres of displacement. The design used a simplified crankshaft which let two opposing pairs of pistons share the same wrist pin. As a result, the crankshaft was both shorter (minimizing vibration issues at speed), and lighter. Levavasseur also had developed a simple fuel injection system that fed the cylinders equally and proved an excellent fuel-air mixture in theory; in practice, however, it proved extremely sensitive to the slightest contamination…dirt, a small bug, or other detritus.

On July 19, 1909, Hubert Latham set out from Calais before dawn, with beautiful weather and a slight tailwind. Already favored by the odds-makers as the man to win, victory seemed firmly in his sight. All along the route, ships from both the French and British navies, as well as work and pleasure boats waited for Latham, waving at the tiny monoplane as it passed overhead. Ah, life was good!

On July 19, 1909, Hubert Latham set out from Calais before dawn, with beautiful weather and a slight tailwind. Already favored by the odds-makers as the man to win, victory seemed firmly in his sight. All along the route, ships from both the French and British navies, as well as work and pleasure boats waited for Latham, waving at the tiny monoplane as it passed overhead. Ah, life was good!

Then, with the fabled White Cliffs of Dover sparkling in the rising sun, almost close enough to touch, the engine quit. Latham spent a frantic few seconds trying to clear the blockage before he realized it was all over.

Six miles from his destination, Hubert Latham earned the dubious honor of making the first landing at sea. When picked up by a spotter boat, Hugh was sitting high and dry in the boat-like fuselage, smoking a cigarette with studied insouciance. The unusually-shaped fuselage had done its work well; there was minimal damage. At least, until the recovery crew tried to bring the airplane on-board, and nearly destroyed it. By the time the damage had been repaired so Latham could attempt his second flight, another challenger had appeared.

Six miles from his destination, Hubert Latham earned the dubious honor of making the first landing at sea. When picked up by a spotter boat, Hugh was sitting high and dry in the boat-like fuselage, smoking a cigarette with studied insouciance. The unusually-shaped fuselage had done its work well; there was minimal damage. At least, until the recovery crew tried to bring the airplane on-board, and nearly destroyed it. By the time the damage had been repaired so Latham could attempt his second flight, another challenger had appeared.

Louis Blériot was an old hand at aviation by this time. As careful and studied as Latham was bold and dashing, Blériot was already an established pilot and aircraft manufacturer.

Louis Blériot was an old hand at aviation by this time. As careful and studied as Latham was bold and dashing, Blériot was already an established pilot and aircraft manufacturer.

In 1903, Blériot along with another aviation pioneer, Gabriel Voisin, had formed an aeroplane company. Blériot was already successful, and had made a small fortune with from a business creating acetylene lamps for carriages, autos, and bicycles.

Over the next five and a half years, Blériot perfected his design, a monoplane with the engine the front and the tail in the back, a light, simple, and strong design. Control was through wing warping and a standard rudder and horizontal tail, and he offered aircraft for sale in magazines in Europe and the US.

Unlike the complex, water-cooled V-8 which powered Latham’s Antoinette, Blériot chose a radial engine, a 3-cylinder Anzani which had the cylinders arranged like the petals of a flower, each one finned for maximum cooling.

Unlike the complex, water-cooled V-8 which powered Latham’s Antoinette, Blériot chose a radial engine, a 3-cylinder Anzani which had the cylinders arranged like the petals of a flower, each one finned for maximum cooling.

Unlike the rotary engines which would be the primary powerplants for aircraft into the early 1920s, the radial did not spin. While this made handling easier, it also meant the engine was more prone to overheating.

Blériot had his own share of difficulties, managing to crash his selected aircraft (a Type VIII) and burn his foot the day shortly before the race. He didn’t see this as a detriment, however: the nurses in Calais hospitals were well-known for their beauty. As a result of this event, however, Blériot would be flying in his newest model, the Type IX.

At 4:30 the morning of the race, Blériot pulled on his breeches, leather coat, and grabbed his goggles and helmet. He strode out to walk around his airplane. Something was up. His was the only plane on the field. Where was Latham?

Well, Blériot decided, no time to lose, a race is a race. A simple check, a swing of the prop, and Blériot, like Lindbergh 18 years later, faced his first obstacle before he had left the runway: telegraph wires. Blériot carefully adjusted his engine speed for maximum climb and barely cleared them.

He was off and running. Time, 4:33 am. Weather fine. Blériot leveled off at 250 feet (76 metres…he was French, after all), and started flying at a steady 40 mph. A French destroyer below him provided escort. Then, the fickle Channel weather began to act up, tossing the fragile monoplane with the translucent wings about. The Channel waves turned into whitecaps, and rain began to fall.

He was off and running. Time, 4:33 am. Weather fine. Blériot leveled off at 250 feet (76 metres…he was French, after all), and started flying at a steady 40 mph. A French destroyer below him provided escort. Then, the fickle Channel weather began to act up, tossing the fragile monoplane with the translucent wings about. The Channel waves turned into whitecaps, and rain began to fall.

Blériot lost his bearings, his visibility. The destroyer was far behind him. His altitude began to fall, until he was less that 60 feet above the waves. As he stated, “I am alone. I can see nothing at all. For ten minutes, I am lost.” A long time aloft. Then, the radial began to overheat. Blériot had difficulties flying in the rain, but then he began to appreciate the cooling it provided his engine.

Finally, those fabled white cliffs appeared before him, a crack between the dull grey sky and raging sea. He was almost there.

And then, it was done. He touched down in a gust of wind, soaked, tired. His landing gear was badly damaged, and for just a moment, he thought sadly of the cost to repair it. Then, he realized he was now a thousand pounds richer. In 37 minutes, the 37-year-old Blériot had flown just over 22 miles, from Calais to Dover.

Blériot would become famous, an influential aircraft designer and manufacturer, responsible for the famous SPAD fighters used during WWI (see right). On May 21, 1927, Blériot would shake hands with a tired Charles Lindbergh, also worried about the aircraft he had just landed on a muddy Le Bourget field in Paris.

Blériot would become famous, an influential aircraft designer and manufacturer, responsible for the famous SPAD fighters used during WWI (see right). On May 21, 1927, Blériot would shake hands with a tired Charles Lindbergh, also worried about the aircraft he had just landed on a muddy Le Bourget field in Paris.

Blériot died quietly in his sleep in 1936, still active in aviation to the last.

As for Hugh Latham, rumor had it that Levavasseur was supposed to wake the team, but that he overslept. The influential engineer continued to work in aviation until his death in 1922.

Latham’s doctor was wrong. He continued to live life to its fullest, until he had a rather disagreeable experience with a wounded water buffalo while on safari in 1912. His sister felt certain that Hubert had been murdered by unruly bearers, however. Regardless, the end was the same: Latham died with his boots on.

July 25 marked the end of an era for Britain. No longer was she an island. The age of the airplane had officially dawned. Few could doubt the usefulness of these tiny craft now. Within a couple of years, Igor Sikosky, father of the helicopter, would construct airliners complete with open air promenades and walnut paneled smoking lounges (see left), while others would drop the first bombs from aircraft in Turkey. In 1914, the dawn of WWI would end Britain’s illusory protection once and for all as both Zeppelins and aircraft attacked.

July 25 marked the end of an era for Britain. No longer was she an island. The age of the airplane had officially dawned. Few could doubt the usefulness of these tiny craft now. Within a couple of years, Igor Sikosky, father of the helicopter, would construct airliners complete with open air promenades and walnut paneled smoking lounges (see left), while others would drop the first bombs from aircraft in Turkey. In 1914, the dawn of WWI would end Britain’s illusory protection once and for all as both Zeppelins and aircraft attacked.

And a century later, the last of the veterans of that Great War, the war that was promised to end all wars, would die in his sleep at 111. Harry Patch refused to discuss his experiences until he was 100. Even as he passed away, re-enactors planned to fly the English Channel once again…

As an aside, I met Mikael Carlson (mentioned in the BBC article) a couple of years ago at the Sun ‘n’ Fun fly-in. A gentleman who was quite patient with my questions about his plane. I even got to help push it into position at Oshkosh a couple of months later, a memorable experience for an early aviation fan like myself. Yes, in case you’re wondering, almost all of the above is from memory, even though there’s days I’m not quite sure how to spell my name…